Spuyten Duyvil resident wants to bring the oysters back

Who speaks for the oysters?

Kevin Horbatiuk, who is a Spuyten Duyvil resident and an avid oyster advocate.

Oysters, Horbatiuk said, played a prominent role in the rise of New York City. On the New York side of the Hudson River, dozens of smaller waterways feed in, which once made for a perfect habitat for the growth of oysters.

“The Hudson River was destined to become a fertile breeding ground for oysters,” Horbatiuk said.

According to Horbatiuk, people ate oysters along the Hudson River as far back as 550 B.C., as evidenced by the oyster shells they left behind. Humans left behind tall piles of white shells so frequently they gained their own name, middens.

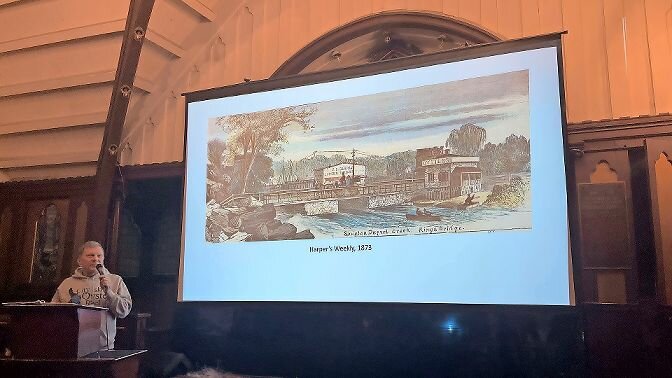

Oyster houses, shacks and carts popped up all over the city as demand for the freshwater mollusks and their shells grew. One such oyster shack was located at the intersection of the streets we now know as West 230th Street and Kingsbridge Avenue.

Historic journal entries detail oysters being consumed at The Kingsbridge Hotel, which resided in Kingsbridge in the late 1800s.

Horbatiuk said, during the excavation of Van Cortlandt Park, a significant number of oyster shells were found, indicating the area was once used as a midden.

Part of what killed the growth of the oyster, aside from overharvesting, he said, was the implementation of combined sewage overflows.

Combined sewage overflows are a now outdated sewage system that was meant to protect the city during a heavy rainfall.

When there’s too much buildup in the sewers, the water does not flow to the treatment plant, where it normally gets processed and separated from the filth of sewage and debris. Instead, the water gets dumped into its designated overflow waterway, which is very often the Hudson River.

But even before the overflow sewage system was in place, Horbatiuk said, the industrialization of the area did its damage.

Railroad construction destroyed middens and added traffic along the city’s waterways began to pollute the oyster’s ecosystem.

Although they can help clean the water in their environment, Horbatiuk said oysters aren’t capable of straining things like oil and debris out of waterways. Instead, oysters pull in water and consume small plankton and particles of organic matter, which helps keep the water clean.

One oyster can filter 55 gallons of water in a day.

According to the Bronx River Alliance’s studies, eastern oysters grow throughout the Bronx River, helping to clean that waterway before it feeds into the East River.

Horbatiuk said he partners with organizations like Billion Oyster Project and City Island Oyster Reef, organizations dedicated to repopulating the city’s oysters for the sake of the environment. In his work with the Billion Oyster Project, Horbatiuk does outreach and education. His work with the City Island Oyster Reef is more hands-on, as he helps to cultivate the reefs the project is developing off the coast of the Bronx.

“Remember what happened with Hurricane Sandy, what we’re doing with the Billion Oyster Project is building reefs that break down the strength of the waves,” Horbatiuk said.

His push for oysters to repopulate the shorelines also takes into account oysters can help protect the erosion of shorelines and ultimately impact storm effects.

While neither organization has plans to build their oyster reefs along the Hudson as far up as Spuyten Duybil, Horbatiuk is glad to see the effort is underway.

More than 120 million oysters “have been introduced to the New York Harbor since 2014,” he said.